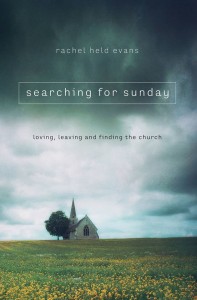

I have been a fan of Rachel Held Evans since I read her first book Evolving in Monkey Town (2010). Soon I was following her blog and when the opportunity arose this winter, I was able to get an advance copy of her newest book Searching for Sunday: Loving, Leaving and Finding the Church.

Even though I don’t have experience in the Evangelical tradition, Evans has the ability to relate her experiences to others from many traditions – even someone raised Catholic like me. Searching for Sunday is a memoir but not a chronological diary. Reflective of her search for rooted authenticity, she organized this book into sections on the seven sacraments.

Each section begins with a sumptuous, earthy meditation on each sacrament that recalls their physicality. Sacraments are done not just assented to. She next shares something of her own experience of the sacrament and stories she has gathered around the country in a way that makes it relatable to many others. This book is for all of Christendom, or at least American Christianity, rather than one fraction or denomination. In each section we are reminded how many traditions mark these sacraments in different ways, whether they care to recognize it in each other’s traditions or not.

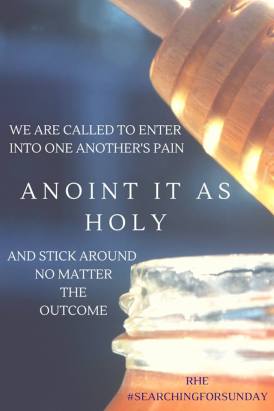

Healing may be implicitly named in only one of the sacraments but there is healing found in every one of them and in every section of this book. In this sense each of these sacraments fulfills a vital need for a full Christian life by providing acceptance (baptism), forgiveness (confession), sustenance (communion), validation (confirmation), purpose (holy orders), healing (anointing of the sick), and companionship (marriage) all held together with grace and love.

Healing may be implicitly named in only one of the sacraments but there is healing found in every one of them and in every section of this book. In this sense each of these sacraments fulfills a vital need for a full Christian life by providing acceptance (baptism), forgiveness (confession), sustenance (communion), validation (confirmation), purpose (holy orders), healing (anointing of the sick), and companionship (marriage) all held together with grace and love.

Receiving the sacrament for the first time is only the beginning. They are meant to be re-experienced for a lifetime. When the church withholds anyone of them them by no longer accepting or sustaining, denying the need for healing, purpose, or companionship, the pain can be intense, leaving scars that last a lifetime. If the church is a peek into the kingdom of heaven on earth, then rejection by the church is a glimpse at hell. What is hell if not the absence of God? We are Christ’s body, if we turn our back on each other is it not inflicting a glimpse at hell on the isolated? Jesus does not abandon or exclude, especially when his church does. How great his disappointment must be. While the LGBT community has been the most visibly discriminated group, many women still struggle to be heard as well as seen in churches that wield the bible like a weapon to enforce their laundry list for conditional acceptance. Searching for Sunday is a balm to sooth the pain, to let you know that you are not alone, validate your pain and begin the healing process.

When we have been hurt, our instinct is to avoid the pain at all costs. Christianity can not be done alone. Even the most holy anchorite who spent their time solely devoted to  prayer, needed the church, depending on their brothers and sisters for spiritual support, physical and sacramental sustenance, a slender line to life. We are no different. Going it alone is just not an option. But, this doesn’t mean that we have to stay where we are rejected, whether that is a parish, denomination or tradition. Perhaps one of the most important messages of this book is that the death of a church (or your relationship to it) is not the end; Jesus is in the business of resurrection. New life in Christ will come, perhaps in unexpected places. The journey will not be easy but Jesus never promised an easy road.

prayer, needed the church, depending on their brothers and sisters for spiritual support, physical and sacramental sustenance, a slender line to life. We are no different. Going it alone is just not an option. But, this doesn’t mean that we have to stay where we are rejected, whether that is a parish, denomination or tradition. Perhaps one of the most important messages of this book is that the death of a church (or your relationship to it) is not the end; Jesus is in the business of resurrection. New life in Christ will come, perhaps in unexpected places. The journey will not be easy but Jesus never promised an easy road.

Do you think it was a coincidence that I was offered to read this book early, over a Lent that I had chosen to step away from my parish over? I don’t. Its now the Easter season and I am glad to be back at my parish, but if I ever do need to step away for longer it won’t be the end of the world either.